Arrival and the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

First of all, THIS POST CONTAINS SPOILERS TO THE FILM. So, if you want to avoid having key parts of the film’s plot and themes ruined for you (like I did, unfortunately, the day before seeing it), then look away now. Honestly, it’s better to go into that cinema not knowing anything about it. So instead of carrying on reading, open a new tab, check your nearest cinema’s viewing times and BUY TICKETS. It’s the best thing you can do for yourself right now, I promise.

One of the main draws of Arrival is that it is well grounded in human emotion, regardless of its heady sci-fi and psychological themes. Some have said that it nailed what Interstellar tried and failed to do in that respect. And I don’t know about you, but I came out crying. The use of Max Richter’s “On the Nature of Daylight” to bookend the film hit me straight in the heart.

Broadly, it’s about worldwide unification, the nature of love and attachment in a deterministic universe, language, perception and what it means to be human. Sounds like a lot, but if you’ve seen the film you can attest that Denis Villeneuve touches on each of these points delicately and poignantly, and you don’t leave the cinema leaving overwhelmed. In this post, I want to talk about two of these themes: language and perception.

Arrival is based on a short story by Ted Chaing called “Story of Your Life”. While I haven’t read the story myself, its synopsis and the film adaptation suggests that it was very much influenced by the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, which posits that human cognition and perception is influenced by / determined by the language that we speak. This is something I learned about in second-year Psychology. Remember Newspeak, from Orwell’s 1984? The idea that if you remove certain words from the local vocabulary, you can exert a subtle kind of authoritarian control over the population? In his dystopian future, Orwell’s characters have no word for the concept of “freedom” or “liberty” and so cannot mentally represent these. From this standpoint, language and thought are 100% intertwined.

There’s little evidence for this extremely restrictive version of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, known as linguistic determinism. Steven Pinker notes that we can all remember back to a time where we’ve been thinking of something but can’t put our finger on the right word to describe it, or where what we’ve written or said isn’t exactly “what we meant to say”. So, in reality, language and thought are somewhat distinct, and Winston Smith can sleep well at night.

However, there are several lines of evidence that suggest that language influences cognition rather than determines it: this is linguistic relativity. It is this weaker version of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis that Ted Chaing’s story and Arrival draw on: when Louise learns that the alien language represents the non-linear way in which they perceive time, her fluency in understanding gives her the ability to see into the future. It may be a little bit of a silly idea, but I like that it’s a fun sci-fi concept based on real psychological research. It’s when the film goes further and asks how you would live a life that you could see stretching out before you in its entirety, that you get hit by the implications of philosophical determinism.

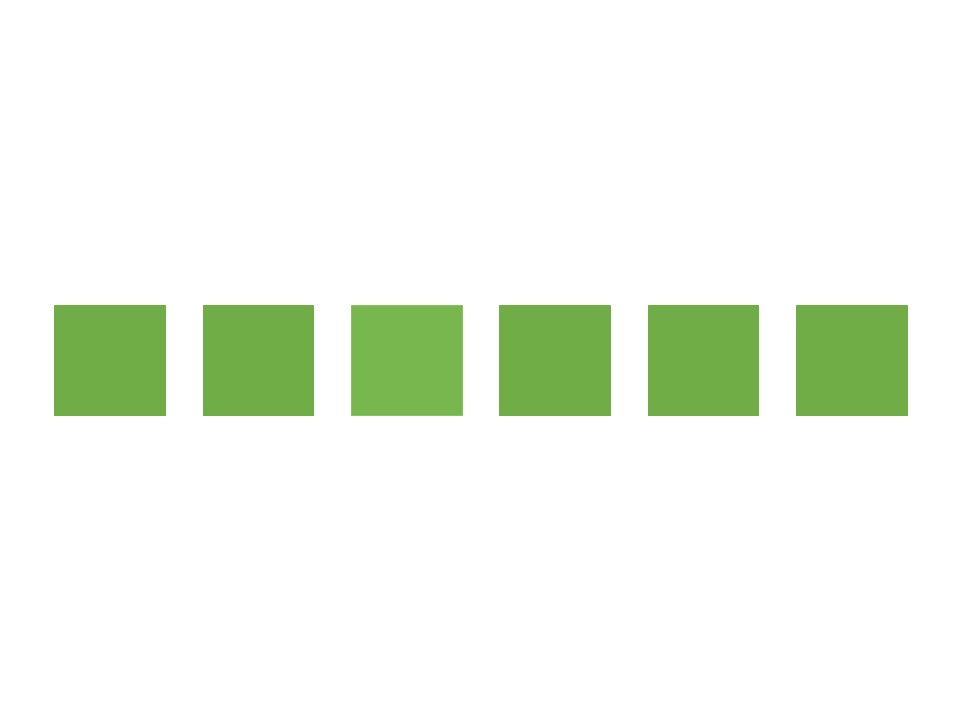

So what is this evidence for language shaping thought? I’ll talk about one interesting set of findings related to colour perception. Some work published by Debi Roberson at the turn of the century looked at the linguistic colour categories of different cultures and how they affect the way people discriminate between colours in perceptual tasks. For example, glance at the colours in the array below. Can you immediately tell which is different?

We English-speakers find this kind of perceptual discrimination hard. In reality, it is the third green from the left that is slightly lighter than the rest, though this does not come to us easily, even when we know which is the odd one out. This is because we only have one word for green, which includes light-greens, dark-greens and everything in between. However, a small tribe called the Hamba in Namibia have several words for green shades. They seem to have little difficulty in picking out odd shades of green from the rest (Roberson et al., 2005). The researchers note that such perceptual discrimination effects are usually found “at the boundaries of existing linguistic categories” (Roberson et al., 2000). It is as if language is facilitating and biasing cognitive discrimination. However, these kinds of effects disappear when participants are asked to do a verbal interference task, such as rehearsing an eight-digit number series (Winawer et al., 2007), suggesting that the effect does not reflect a permanent change to low-level sensory perception.

There’s some other interesting evidence for the effect of language on cognition that I won’t go into in detail here. For example, common ways to express frames-of-reference in a language, either relative to the speaker (“to the right”) or absolute (“facing North”), have been shown to affect performance in spatial rotation problems (Levinson, 1996). Similarly, languages with “one-two-many” counting systems seem to inhibit memory for large quantities of items (Frank et al., 2008). These studies are exciting to read about because they tap into an ancient question: what is it like to look through another person’s eyes?

Arrival asks such questions too, but with the grander backdrop of alien invasion behind it. We come out of the movie theater asking, what would it be like to perceive time as non-linear? What would it be like to be a Heptapod? The struggle that Louise has with communicating with the Heptapods reflects the difficulty we, as humans, have with taking ourselves out of our own shoes and imagining the perceptions of not only other animals but each other too. Rust Cohle from True Detective calls this the “black box” of consciousness. We’re stuck in our own minds. But it’s fun to imagine what the aliens see. It’s that consciousness-escapism that makes Arrival’s aliens - and the film as a whole - so successful and enduring.

References

- Frank, M. C., Everett, D. L., Fedorenko, E., & Gibson, E. (2008). Number as a cognitive technology: Evidence from Pirahã language and cognition. Cognition, 108(3), 819-824.

- Levinson, S. C. (1996). Language and space. Annual review of Anthropology, 353-382.

- Roberson, D., Davies, I., & Davidoff, J. (2000). Color categories are not universal: replications and new evidence from a stone-age culture. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 129(3), 369.

- Roberson, D., Davidoff, J., Davies, I. R., & Shapiro, L. R. (2005). Color categories: Evidence for the cultural relativity hypothesis. Cognitive psychology, 50(4), 378-411.

- Winawer, J., Witthoft, N., Frank, M. C., Wu, L., Wade, A. R., & Boroditsky, L. (2007). Russian blues reveal effects of language on color discrimination. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(19), 7780-7785.