Amotz Zahavi and The Handicap Principle

A very innovative Israeli biologist just recently passed away. His name was Amotz Zahavi, and his work in the 1970s (and since) revolutionised the way we think about animal communication. My impression is that he was somewhat of a renegade in the field of evolutionary biology, creatively fighting against the academic status quo with his ideas. In fact, everyone rejected his theories at first (before they were proved mathematically), but today his outside-of-the-box hypotheses have become the consensus in signalling theory. On Friday, at the age of 89, he died. And yet, searching his name on Google this evening, no news sites seems to be reporting his death, or celebrating his important work. This is sad, but may be because his fame is relatively restricted to academic circles. So I wanted to write something quickly this evening, as a small tribute.

It all starts with this quote from Charles Darwin himself:

“The sight of a feather in a peacock’s tail makes me sick.”

A peacock’s tail is a magnificent sight. I’ve seen one with my own eyes, at a zoo in Rio de Janeiro. So, why did Darwin hate them so much? Well, recall the theory of natural selection. Heritable traits that help individuals survive and reproduce will be preserved, and unfavourable traits will be extinguished. Over time, this will lead to a morphology that is crafted to solve adaptive problems: hands for grabbing, eyes for seeing, etc.

But just look at that thing. How the hell does it help the peacock survive?

In fact, it’s quite the opposite. It seems that the bird’s huge, cumbersome tail actually hinders it. I saw this myself at the zoo. The male has to lug this huge thing around everywhere it goes. And forget about trying to escape from a predator… Imagine trying to run away from a tiger with a parachute dragging you back (!) and you’ll see what I mean. It’s almost as if the tail is maladaptive.

Hence Darwin’s sickness. It was another problem for his theory. But, years later, Amotz Zahavi came up with a solution. Paradoxically, he explained how natural selection could, in theory, actually select for such “handicaps”. And it all comes down to the ways in which animals communicate with one another.

Consider a female peahen choosing a male to mate with. There are many males, but what does she look for in a mate? In crude biological terms, one important quality is high “fitness” (the male’s ability to survive and reproduce). If she chooses a male with high fitness, then together they are likely to sire offspring with high fitness too, hence more successfully propagating her genetic material. Great, let’s pick the one with high fitness. Right. But… how does the female know which male has higher genetic fitness? After all, she can’t see into the genome.

This is where the communication comes in. It is now in the male’s interest to signal to the female that they have high fitness. The signal could be anything: a morphological trait, a behaviour, etc. Let’s say, for example, that the trait is to have a blue tail. So now, all the high fitness males have blue tails. Perfect. This now gives the female a chance to narrow her search for a mate down to just the males with blue tails.

However, the problem with just having a blue tail as a signal is that it’s something that low quality individuals can also adopt. It is easy, and now adaptive, for lower fitness individuals to also adopt blue tails, because they’ll then be more likely to get picked as a mate. Here, the signal is not honest. The low fitness individuals are cheating the system! Suddenly, everyone has blue tails and the female is none the wiser: we’re back to square one.

To be ‘evolutionarily stable’, any signalling system must somehow be honest, otherwise there is a danger of being cheated by liars, as above. Amotz Zahavi’s insight was simple. Honesty can be ensured with very costly signals; so costly that individuals of low fitness simply cannot afford to adopt them. This is known as the handicap principle.

Let’s take this and now say that the signal of high fitness is the huge tail shown in the picture above. For high fitness males, this is no bother. Because they have ample genetic quality, they can afford to take this burden of a tail and still survive no problem. Low fitness males, however, cannot afford to express this signal: if they did, they may likely die at the hands of hungry predators that they can no longer outrun. Thus, only high fitness males can afford the signal, and so this signal is kept an honest, reliable, unfakeable advertisement of quality. When females start choosing on the basis of these signals, boom, we have an honest signalling system and the evolution of a costly, sexually selected trait.

Counter-intuitive, but it works! So Darwin need not feel sick at the sight of the peacock’s tail. Amotz Zahavi understood that it was just a logical extension of his theory of sexual selection.

The handicap principle can also be extended outside of a sexual context. There is a curious (and hilarious) behaviour in gazelles that are being chased by predators called “stotting”, where the individual will make a series of leaps into the air, in full view of the predator. This is initially puzzling, as the gazelle could do much better to simply sprint away as fast as possible and keep to the ground. However, costly signalling theory shines light on this behaviour: it could be viewed as a signal to the predator, saying “Look at me! I am so athletic that I can afford to jump up and down while evading you, there’s no point trying to catch me. You may as well try and catch one of these other muppets.”

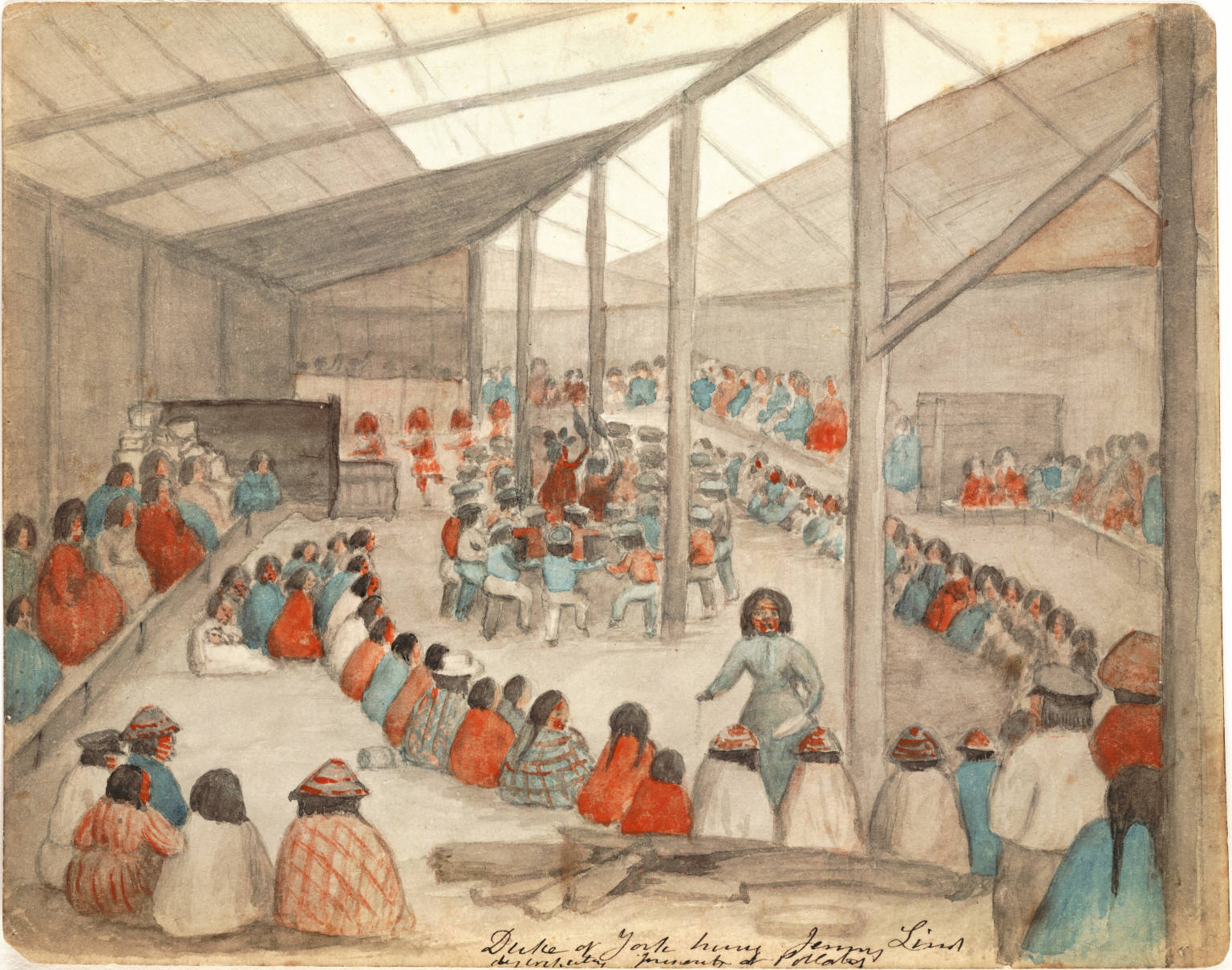

Zahavi also extended his theory to humans, and the famous “potlatch” ceremonies of various indigenous peoples. In these ceremonies, various chieftains get together and compete to destroy goods and wealth in a huge bonfire, in a form of ‘conspicuous consumption’. Winning a potlatch can confer huge status benefits to the chieftain. Through the lense of costly signalling, this kind of behaviour can be viewed as a handicap, a costly signal of quality and wealth, that poorer chieftains cannot match.

While not all biologists today agree on the scope of costly signalling that Amotz Zahavi insisted upon, it is clear that the handicap principle is an important foundation on which animal communication theory sits. Even if it doesn’t apply to all forms of signalling, it sparked a debate and got biologists talking about (and modelling) how signals could be honest and reliable, and therefore evolutionarily stable (signal honesty in the context of cooperation is actually the topic of my current Masters thesis!). Zahavi’s work was revolutionary, and the handicap principle will continue to be studied for many years to come. RIP to a legendary biologist!