COVID-19 Moral Messaging

Recently, Everett et al. published a pre-print studying the effects of different moral messages on US participants’ intentions to engage in protective-behaviour relating to COVID-19. With many countries around the world transitioning into full-lockdown status, this work is timely. It is also a testament to the power of open science: important scientific ideas can be disseminated quickly and efficiently. As of 27th March 2020, the pre-print has been downloaded 832 times (since 21st March 2020).

Another advantage of open science is that it immediately allows other researchers access to raw data to conduct alternative analyses. I report such an alternative analysis here. This alternative analysis builds on the previous work in a number of ways:

- I treat the outcome variable as ordinal. This is crucial because treating ordinal variables as continuous, as Everett et al. did, can distort effect size estimates. As the effect sizes are small in the original pre-print, it is important to see whether the effects hold when using ordinal regression. This technique is also preferred to standard regression when there are ceiling or floor effects, as there are in this dataset.

- I model participants and questions as random effects. In order to generalise beyond this specific sample and the specific questions asked in the study, we need to follow a random effects approach. This approach can also easily scale up to multi-country studies, as it allows us to nest individuals within countries: this is the next step for the research team.

But first, let’s load the dataset in long-form.

# can access original data here: https://osf.io/f74sz/

d <- readd(d)

d %>%

select(ID, message_condition, source_condition, behaviour, response) %>%

head(n = 20)

## # A tibble: 20 x 5

## ID message_condition source_condition behaviour response

## <int> <fct> <fct> <chr> <int>

## 1 1 Utilitarian Leader self_wash_hands 7

## 2 1 Utilitarian Leader self_avoid_gatherings 7

## 3 1 Utilitarian Leader self_isolate 4

## 4 1 Utilitarian Leader self_share_post 5

## 5 2 Non-Moral Citizen self_wash_hands 6

## 6 2 Non-Moral Citizen self_avoid_gatherings 7

## 7 2 Non-Moral Citizen self_isolate 7

## 8 2 Non-Moral Citizen self_share_post 1

## 9 3 Deontological Leader self_wash_hands 5

## 10 3 Deontological Leader self_avoid_gatherings 5

## 11 3 Deontological Leader self_isolate 3

## 12 3 Deontological Leader self_share_post 1

## 13 4 Virtue Citizen self_wash_hands 7

## 14 4 Virtue Citizen self_avoid_gatherings 5

## 15 4 Virtue Citizen self_isolate 3

## 16 4 Virtue Citizen self_share_post 6

## 17 5 Utilitarian Leader self_wash_hands 6

## 18 5 Utilitarian Leader self_avoid_gatherings 6

## 19 5 Utilitarian Leader self_isolate 4

## 20 5 Utilitarian Leader self_share_post 6

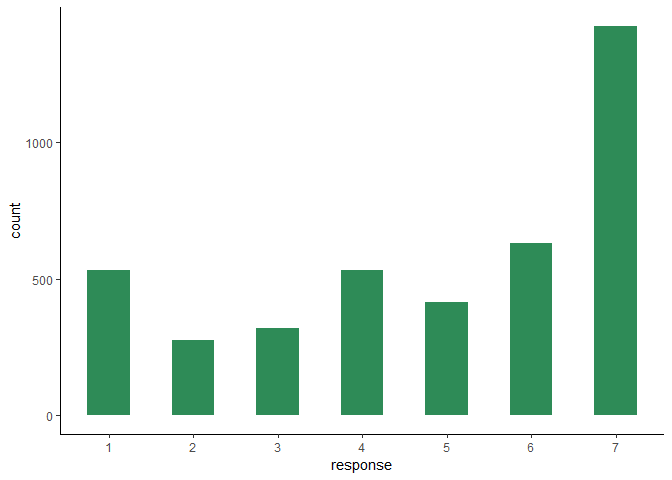

In particular, we’re interested in the response column.

This is accumulated Likert-scale responses to four “behavioural

intentions” questions after reading a social-media post with a

particular moral message. The behavioural intentions questions are (1)

washing hands, (2) avoiding public gatherings, (3) staying at home, and

(4) sharing the social-media post. I have accumulated these responses

into a single response column, as we can then model all the

behavioural intentions questions at once, treating the different

questions as random effects. As you can see from the histogram, the

modal choice is 7 (extremely likely to act). This ceiling effect makes

an ordinal approach to these data necessary.

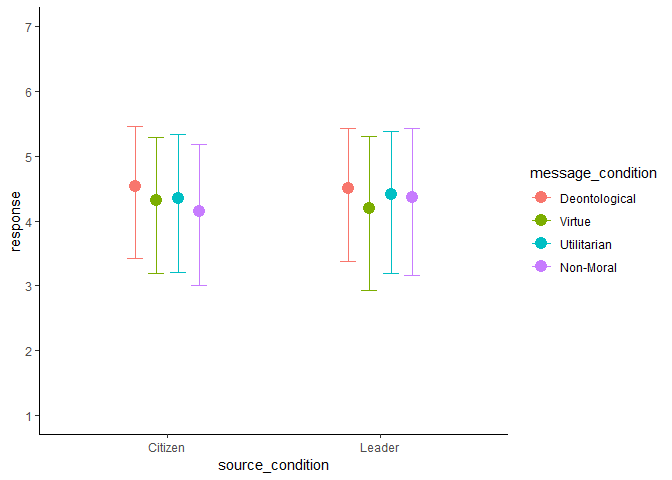

I focus on behavioural intentions for this analysis. In a between-subjects experiment, the original pre-print manipulated two variables. First, the source of the message was manipulated (from a citizen, or from a leader). Second, the type of message was manipulated (non-moral, deontological, virtue, utilitarian). The research aims to uncover whether responses differ in these different conditions.

I fitted five Bayesian ordinal multilevel models to these data using the brms package:

m1- Null modelm2- Main effect of source conditionm3- Main effect of message conditionm4- Interaction between source and message conditionm5- Interaction between source and message condition (with controls)

These models include response as the ordinal DV, participant ID

(1-1032) as a random intercept, and also behaviour (1-4) as another

random intercept. Main effects and interactions for source and message

are also included as random slopes within behaviour, meaning that each

behaviour has its own effect of source and message. For example, the formula

for model m4 is response ~ 1 + source_condition*message_condition +

(1 + source_condition*message_condition | behaviour) + (1 | ID).

Before digging into the models, what does model comparison tell us? We use leave-one-out cross-validation to compare models.

# only m1-m4, m5 has fewer data points due to listwise deletion

loo_compare(m1, m2, m3, m4)

## elpd_diff se_diff

## m2 0.0 0.0

## m1 -0.5 3.0

## m3 -1.9 4.0

## m4 -2.2 3.8

None of the models differ from the null model, suggesting that the source or the moral framing of the message do not affect people’s responses to questions about their behavioural intentions.

Let’s visualise the predictions of the interaction model m4 to see

this for ourselves.

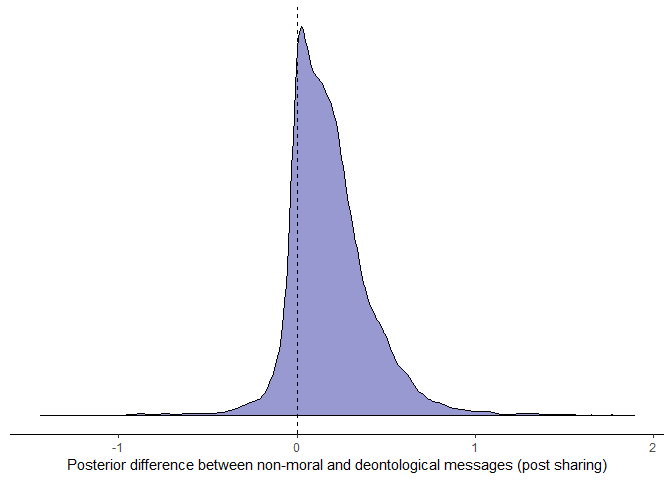

The above plot lumps the four behavioural intentions together. However, one key finding from the original pre-print is that participants “reported significantly stronger intentions to share the deontological message” compared to the control condition. Let’s visualise the posterior difference between non-moral and deontological messages for the post-sharing question specifically.

85% of the posterior distribution is above zero, which is not enough to claim that deontological messages encourage greater post-sharing over non-moral messages. This finding remains when including demographics controls (not shown here).

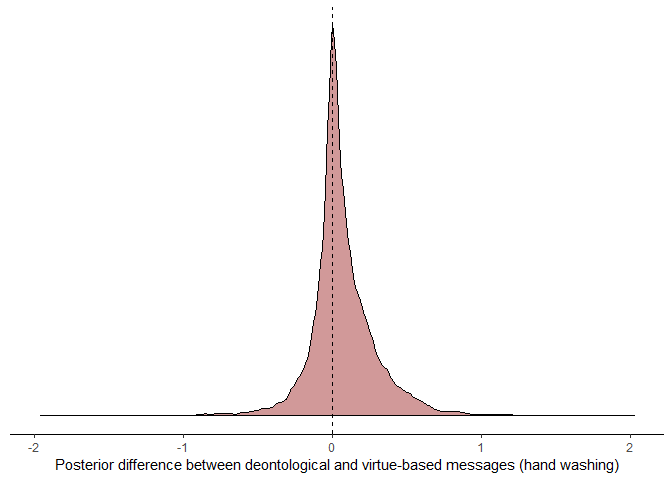

Another finding from the paper is that, when including demographic controls, “deontological messages were more effective than virtue-based messages” at encouraging hand washing. We follow the same approach above to evaluate this claim.

63% of the posterior distribution is above zero, which again is not enough to claim that deontological messages encourage greater hand-washing over virtue-based messages.

However, we do replicate the demographic effects from the original

paper. Model m5 reveals that US participants who are younger, male,

white, more educated, more conservative, and less religious are the

ones that are less likely to engage in protective behaviours (not shown

here).

In sum, while I applaud the speedy efforts of Everett et al. to

publish their pre-print on this important topic so quickly,

unfortunately I do not think the data, when properly modelled, supports

the conclusion that “focusing on duties and responsibilities toward

family, friends and fellow citizens could be an effective strategy for

convincing others to adopt behaviors that slow the spread of COVID-19 in

the US” (see this

tweet).

Maybe I will be proved wrong when this research is scaled up to include

individuals from other countries. For these multi-country studies, I

urge the researchers to build on the approach I have used here by: (1)

using all the available data inside a single model, (2) correctly

treating the DV as ordinal, and (3) nesting individuals within countries

in a random effects framework (i.e. (1 | Country/ID)). This will help

us make the kinds of broad generalisable inferences that this crisis

requires of us.

Code for this post can be found here: https://github.com/ScottClaessens/covidMoralMessaging

Session Info

sessionInfo()

## R version 3.6.2 (2019-12-12)

## Platform: x86_64-w64-mingw32/x64 (64-bit)

## Running under: Windows >= 8 x64 (build 9200)

##

## Matrix products: default

##

## locale:

## [1] LC_COLLATE=English_New Zealand.1252 LC_CTYPE=English_New Zealand.1252 LC_MONETARY=English_New Zealand.1252 LC_NUMERIC=C LC_TIME=English_New Zealand.1252

##

## attached base packages:

## [1] stats graphics grDevices utils datasets methods base

##

## other attached packages:

## [1] tidyselect_1.0.0 twitterwidget_0.1.1 forcats_0.4.0 stringr_1.4.0 dplyr_0.8.4 purrr_0.3.3 readr_1.3.1 tidyr_1.0.2 tibble_2.1.3 ggplot2_3.2.1 tidyverse_1.3.0 drake_7.10.0.9000 brms_2.11.6 Rcpp_1.0.3

##

## loaded via a namespace (and not attached):

## [1] colorspace_1.4-1 ggridges_0.5.2 rsconnect_0.8.16 markdown_1.1 base64enc_0.1-3 fs_1.3.1 rstudioapi_0.11 farver_2.0.3 rstan_2.19.2 DT_0.12 fansi_0.4.1 mvtnorm_1.0-11 lubridate_1.7.4 xml2_1.2.2 bridgesampling_0.8-1 knitr_1.28 shinythemes_1.1.2 bayesplot_1.7.1 jsonlite_1.6.1 broom_0.5.4 dbplyr_1.4.2 shiny_1.4.0 compiler_3.6.2

## [24] httr_1.4.1 backports_1.1.5 assertthat_0.2.1 Matrix_1.2-18 fastmap_1.0.1 lazyeval_0.2.2 cli_2.0.1 later_1.0.0 htmltools_0.4.0 prettyunits_1.1.1 tools_3.6.2 igraph_1.2.4.2 coda_0.19-3 gtable_0.3.0 glue_1.3.1 reshape2_1.4.3 cellranger_1.1.0 vctrs_0.2.3 nlme_3.1-144 crosstalk_1.0.0 xfun_0.12 ps_1.3.2 rvest_0.3.5

## [47] mime_0.9 miniUI_0.1.1.1 lifecycle_0.1.0 gtools_3.8.1 zoo_1.8-7 scales_1.1.0 colourpicker_1.0 hms_0.5.3 promises_1.1.0 Brobdingnag_1.2-6 parallel_3.6.2 inline_0.3.15 shinystan_2.5.0 yaml_2.2.1 gridExtra_2.3 loo_2.2.0 StanHeaders_2.21.0-1 stringi_1.4.6 dygraphs_1.1.1.6 filelock_1.0.2 pkgbuild_1.0.6 storr_1.2.1 rlang_0.4.4

## [70] pkgconfig_2.0.3 matrixStats_0.55.0 evaluate_0.14 lattice_0.20-38 rstantools_2.0.0 htmlwidgets_1.5.1 labeling_0.3 processx_3.4.2 plyr_1.8.5 magrittr_1.5 R6_2.4.1 generics_0.0.2 base64url_1.4 txtq_0.2.0 DBI_1.1.0 pillar_1.4.3 haven_2.2.0 withr_2.1.2 xts_0.12-0 abind_1.4-5 modelr_0.1.5 crayon_1.3.4 utf8_1.1.4

## [93] rmarkdown_2.1 progress_1.2.2 grid_3.6.2 readxl_1.3.1 callr_3.4.2 threejs_0.3.3 webshot_0.5.2 reprex_0.3.0 digest_0.6.23 xtable_1.8-4 httpuv_1.5.2 stats4_3.6.2 munsell_0.5.0 shinyjs_1.1