Cultural Evolution

Cultural phylogenetics and the emergence of social norms

In the Language, Culture, and Cognition lab at the University of Auckland, one of our areas of expertise is creating and employing language phylogenies to study the evolution of human culture. For example, a phylogenetic tree of Indo-European languages shows that English is more closely related to German than it is to Spanish, Latvian, or Armenian. Once such ancestral relationships between languages are established, we can use these to study how human cultures, from small-scale societies to modern nation states, have evolved over time.

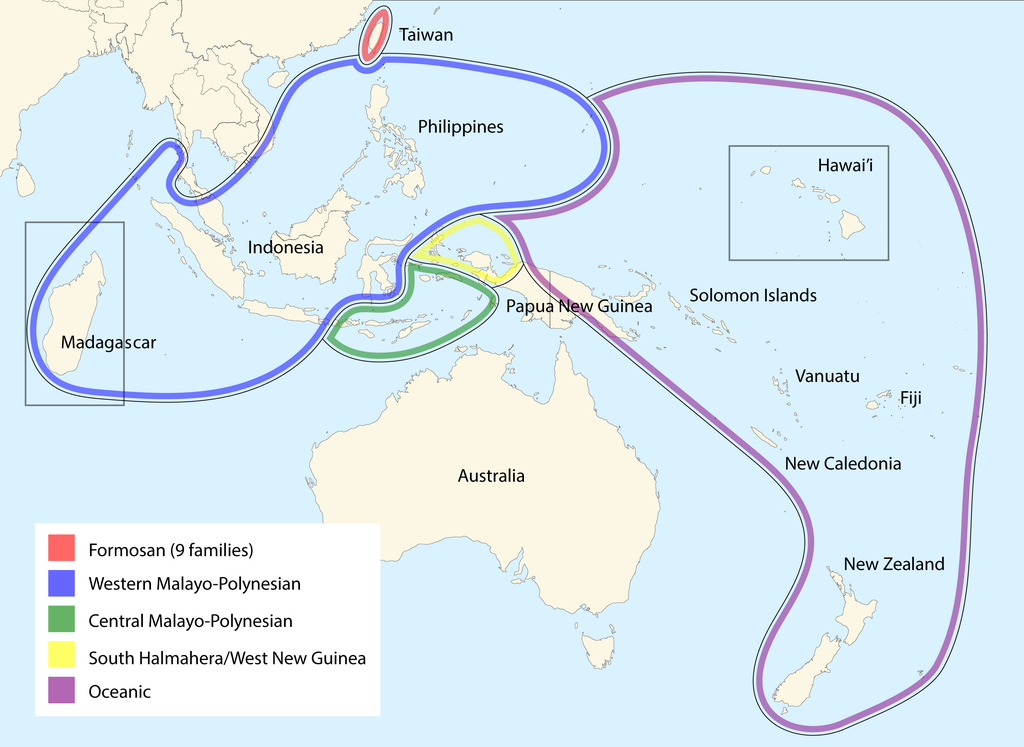

In one project, we studied 97 Austronesian societies speaking different languages (see paper here). By using a phylogenetic tree of the Austronesian language family, we were able to track the coevolution of institutions of authority in these societies over time. In particular, we found that two forms of institutionalised authority — political and religious authority — coevolved over time, meaning that as one form of authority began to encompass a larger group in these societies, so too did the other form of authority.

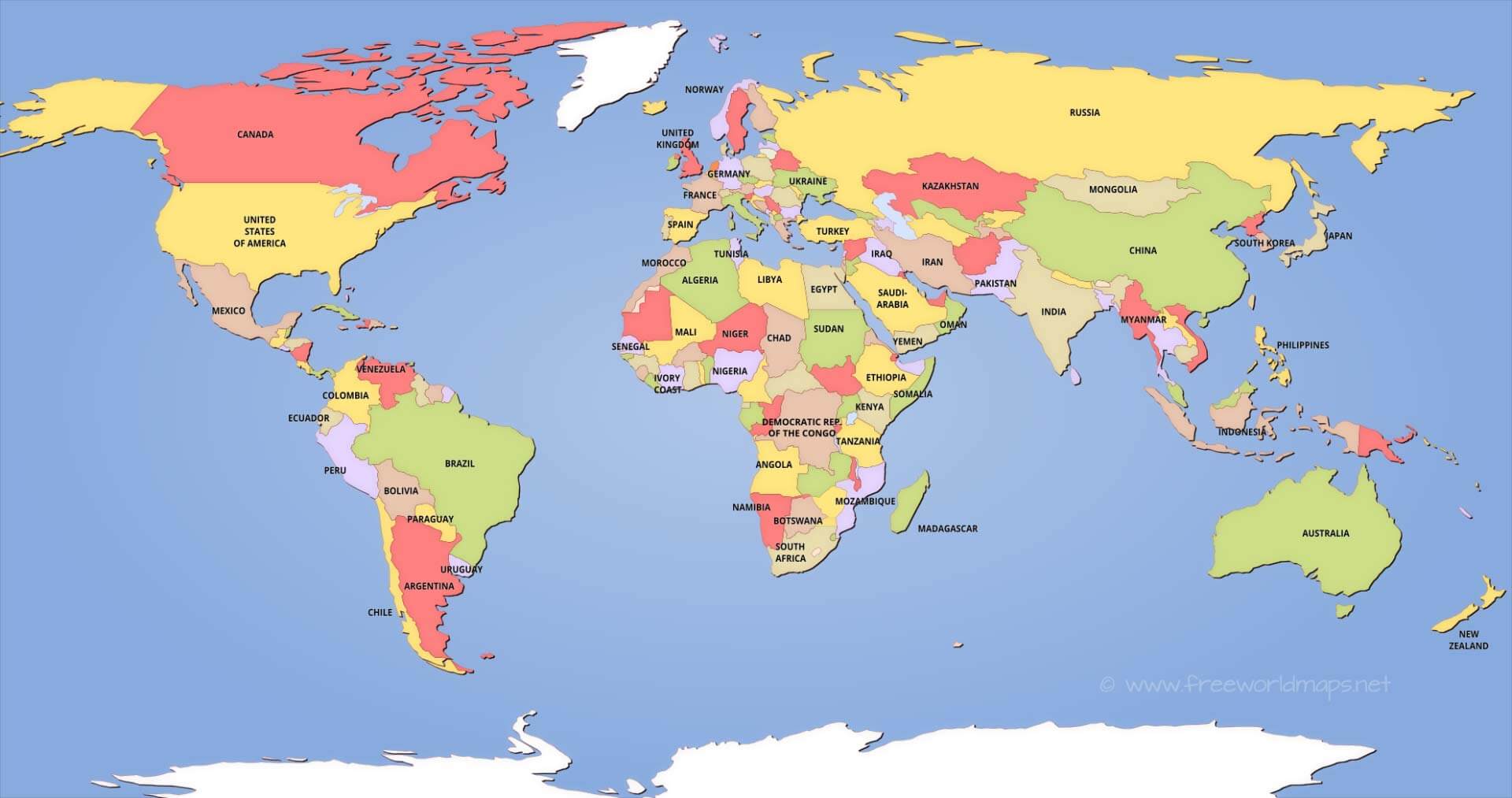

Language phylogenetics can also contribute to research on modern nation states. In another study, we found that nations that are closely culturally related — for example, the United Kingdom and Germany, who speak the closely-related languages English and German — tend to be similar in other ways, such as having similar levels of GDP per capita or similar cultural values. The same is also true for spatial proximity: geographic neighbours tend to be more similar to one another than geographically distant nations. This similarity is likely due to processes of cultural evolution over time, either from deep cultural inheritance from shared ancestors or from more recent diffusion of traits among neighbouring nations. In the paper (see here), we argue that it is crucial to control for these sources of non-independence among nations. Without suitable controls, this non-independence may lead researchers to falsely infer national-level correlations that do not exist.

I have also studied the evolution of culture among individuals rather than societies. In a collaboration with my US colleagues, we studied the real-time emergence of social norms governing mask wearing during the COVID-19 pandemic (see paper here). Using two years of longitudinal data collected from 2020 to 2022, we found that mask wearing norms developed quickly in the United States in response to public health recommendations. Our analyses also suggest that the emergence of these norms, especially descriptive norms (i.e., seeing if others are wearing masks), had a causal effect on mask use.

Further Reading

Claessens, S., Kyritsis, T., & Atkinson, Q. D. (2023). Cross-national analyses require additional controls to account for the non-independence of nations. Nature Communications, 14(1), 5776.

Heiman, S. L., Claessens, S., Ayers, J. D., Guevara Beltrán, D., Van Horn, A., Hirt, E. R., … & Todd, P. M. (2023). Descriptive norms caused increases in mask wearing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 11856.

Sheehan, O., Watts, J., Gray, R. D., Bulbulia, J., Claessens, S., Ringen, E. J., & Atkinson, Q. D. (2023). Coevolution of religious and political authority in Austronesian societies. Nature Human Behaviour, 7(1), 38-45.